Women of Trachis

Women of Trachis by Sophocles

The least developed of all Sophocles’ tragedies in terms of structure and action, Women of Trachis dramatizes the unfortunate and accidental death of Ancient Greece’s greatest hero, Heracles. The play is set before the royal palace at Trachis, fifteen months since the region’s king, Heracles, has left his home to go on one of his adventures. His queen, Deianira, is worried due to the lack of news, so she sends her son Hyllus to find out what has become of Heracles. Hyllus, however, already knows this much: after serving as a slave for a year at the court of queen Omphale, Heracles is currently fighting in Oechalia against King Eurytas, the author of his previous demise. Determined to help him, Hyllus leaves for Oechalia. Soon after, Heracles’ herald Lichas arrives at the court of Trachis with a few female captives, one of whom is none other than Iole, King Eurytas’ daughter. After some inquiring, Deianira learns from Lichas that Heracles has conquered Oechalia not because of Eurytas’ offense, but because he wanted the country’s princess for himself. Disheartened, Deianira sends Heracles a festal robe anointed with the blood of the centaur Nessus, who had told her, years before and with his dying breath, that his blood is a love charm which has such power to make Heracles never look upon any other woman. That is precisely what happens, but not in line with Deianira’s expectations. Namely, as Hyllus soon reports, the robe has poisoned Heracles, and he is in such pain and agony that he is better off dead. Upon realizing what she has done, Deianira kills herself. After being brought home to Trachis, Heracles asks his son Hyllus to marry Iole and then orders him to light a funeral pyre that will put an end to his suffering.

Date and Historical Background

Less developed than all of Sophocles’ other surviving plays, Women of Trachis was for a long time considered Sophocles’ earliest surviving play, first produced sometime around 451. However, due to several thematic similarities to Oedipus Rex and a few structural parallels with some popular plays by Euripides from the period, nowadays, most scholars tend to argue for a later date, one in the 430s.

Characters and Setting

Characters

• Deianira, daughter of Oeneus, wife of Heracles

• Nurse of Deianira’s children

• Hyllus, the oldest son of Deianira and Heracles

• Messenger, coming from Euboea

• Lichas, Heracles’ herald

• Chorus of Trachinian women

• Euboean captives, among them Iole (silent role)

• Attendants of Heracles

Setting

The scene is laid before the palace of Heracles and Deianira at Trachis.

Summary of Women of Trachis

Prologue

Alone with the nurse of her children at the palace of Trachis, Deianira recalls the misfortunes of her past life and expresses anxiety over the absence of her beloved husband, Heracles. It is over a year—fifteen months precisely—since he has left home, and as much time has passed since she last heard of him. The nurse suggests Deianira that she sends her oldest child, Hyllus, to search for his father. Just then Hyllus arrives with some news: after having served one year at the court of Queen Omphale of Lydia, Heracles is currently in Euboea fighting against King Eurytus of Oechalia. Deianira then remembers that Heracles has left with her some “sure oracles concerning that land” which suggest that “either he shall meet the end of his life there, or, after taking on this contest, he shall thereafter, at least, enjoy a happy life for its duration.” Hyllus immediately determines to join his father in Euboea, and leaves for that purpose.

Parodos (Entrance Song)

The Chorus of fifteen Trachinian maidens enters. They are full of sympathy for Deianira, who, they have heard, is pining inconsolably for her husband. They remind her, however, that life consists of both sorrows and joys, and that the former shall make room for the latter very soon.

First Episode

Moved, Deianira reveals to the Trachinian maidens the real source of her anxieties: before going away, Heracles has told her that if he is not back in fifteen months, she should consider him dead. With the period in question now due, Deianira fears for the worst.

Fortunately, a Messenger arrives with some great news: Heracles is victorious and will soon come home. Lichas, Heracles’s herald, should have relayed to her the glad tidings by now, but his progress has been slowed down by the excited Trachinians. Overjoyed, Deianira calls for a song: the Chorus responds with a short paean.

Even before they can finish it, Lichas arrives, a few maidens behind him. He tells Deianira that they are “captives whom [Heracles] selected as choice spoils for himself and for the gods when he sacked the city of Eurytus.” He did that, Lichas informs Deianira, as an act of revenge, since it was a ploy of Eurytus which led to Heracles being sold into one-year servitude in Lydia.

Deianira is happy, but also strangely interested in one of the captives. “Unfortunate girl,” she asks her, “who are you? Are you without a man, or are you a mother? To judge by your appearance, you are untried in those roles, but someone of noble birth.” Lichas disinterestedly says that he has no information on the girl’s family and proceeds to conduct the slave women into the palace.

The Messenger takes Deianira aside and tells her the truth: that girl is indeed a noblewoman and it is none other than Iole, the princess of Oechalia. It was her beauty and Eurytus’ unwillingness to give the girl to him that incited Heracles to sack his city. Confronted upon his return with this information, Lichas confirms the story: he didn’t tell it outright so as to not cause sorrows to anyone. Deianira doesn’t seem too bothered, though. In fact, she just requests that Lichas follows her into the house so that she can give him a message and a gift for Heracles.

In the second choral song (the first stasimon), the Trachinian women celebrate the power of love and recall the days when, overwhelmed by it, Heracles fought with the river god Achelous for the admiration and respect of Deianira.

Second Episode

“I have received a maiden,” says Deianira upon reappearance, “into my home, just as a mariner takes on cargo. And now we are two, a pair waiting under a single bedspread for one man's embrace… To live with her, sharing the same marriage—what woman could endure it?”

Strangely enough, however, Deianira is not mad with Heracles; she says that she doesn’t know how to be. Her only wish is for Heracles to love her back and, hopefully—she reveals to the Chorus—she might just be able to regain his heart.

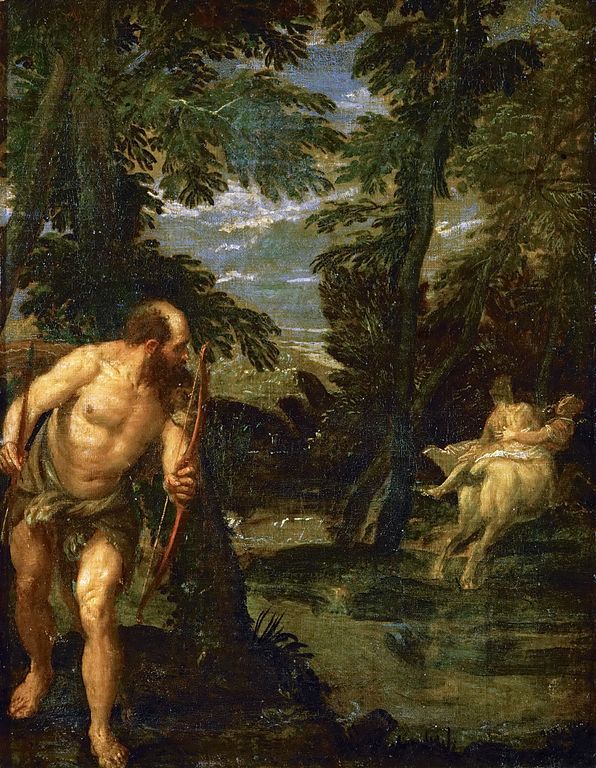

Long ago, she explains, while carrying her over the river Evenus, the Centaur Nessus tried touching her lustfully, and Heracles shot him with his famous unerring arrows dipped in the toxic blood of the Lernaean Hydra. “Child of aged Oeneus,” Nessus said to Deianira with his dying breath, “if you gather with your hands the blood clotted round my wound, you will have a charm for the heart of Heracles, so that he will never look upon any woman and love her more than you.”

Unquestioning, Deianira did just that and has kept the blood safely through all these years. Now, she has applied it on the inside of a robe—the gift she intends to send to Heracles by way of Lichas. She tells him that Heracles must wear the robe on the day he intends to make a thank-offering to the gods. Lichas promises loyalty, and they both leave, in two opposite directions.

In the second stasimon, the Chorus expresses hope that Heracles will not only return victorious but also with a heart filled with a new-found love for his dutiful wife.

Third Episode

Distraught, Deianira reenters from the palace, fearing that soon she might learn that she has “done a great wrong.” “Tell us the cause of your fear,” the Chorus implores. And Deianira explains: “The tool with which I was just now anointing the festal robe, a white tuft of fleecy sheep's wool, has disappeared, eaten away by no animal in the courtyard, but self-devoured and self-destroyed it crumbled down over a stone slab.” In other words, Deianira has legitimate fears that Nessus’ blood might have been just as poisonous and deadly as Heracles’ arrows, and that, instead of a bridal gift, she might have sent her husband a parting one.

As the Trachinian women comfort her, Hyllus arrives from Euboea in a roused and agitated state. “You have killed your husband, my father—my father,” she shouts, and, upon being asked by the stricken Deianira what had happened, proceeds to tell the full story. Hyllus was there when Heracles put on the festal robe in front of the altar before making his offerings to the gods. However, just as soon as the flames rose from the sacrifice, the robe tightly gripped his body, and Heracles started “convulsing down to the ground and up into the air as he shouted and cried out.” In agony, he killed Lichas and, seeing his frenzied state, no man dared to come close to him after that. He has since been laid in a boat, heading to Trachis now; Deianira should see him soon. After denouncing her as his mother, Hyllus storms to the palace, where Deianira heads as well, taken aback and wordless.

In the third stasimon, the Chorus sings of how Nessus has found a way to kill Heracles even after his own death and how there is no way to escape the ancient prophecies or Aphrodite’s power.

Fourth Episode

The Chorus leads us ominously into the fairly short fourth episode, by announcing, at the end of their song, that they have heard “some cry of grief rushing through the house.” The Nurse rushes out from the palace and, distressed, explains the origin of the sound: Deianira has killed herself with a sword and is now bitterly mourned by her son, who has learned, a tad too late, that she was just an innocent tool of destiny.

In the fourth stasimon, the Trachinian women express their sorrow at the news and their anguish at the thought that, very soon, Heracles should also arrive, and they are the only ones left to behold his tortured state. “Which disaster shall I bewail first?” they sing. “Which is more to be pitied? In my grief I cannot decide...”

Exodos (Exit Song)

Soon after, a mournful procession arrives, carrying Hercules on a litter. Hyllus, walking beside the litter, grieves the misfortunate end of his father, and this awakes Heracles. After realizing where he is, he begs the frightened bystanders around him to kill him as an act of mercy. In a moment of respite, he ruminates upon his past life and the irony that, after defeating so many monsters, he is doomed to die at the unarmed hands of a weak woman.

Hyllus uses a brief moment of silence to announce his mother’s death and to inform his father of her innocence: deceived by the dying Nessus, she thought the robe was a love-charm and not a murder weapon. Heracles has now understood everything: “Go, my son!” he shouts, “Your father is no more.” On being asked to tell more, he reveals that his father had told him long ago that he “would perish by no creature that had the breath of life, but by one already dead, a dweller with Hades.” Moreover, it seems that Heracles has misinterpreted yet another oracle—the one mentioned by Deianira at the beginning of the play—prophesizing his “release” from the toils laid upon him. “I expected prosperous days,” he says mournfully, “but the meaning, it seems, was only that I would die. For toil comes no more to the dead.”

Heracles commands Hyllus to carry him to the summit of Mount Oeta, a place sacred to Zeus, and there to prepare for him a funeral pyre. He also orders him to marry Iole which, after some hesitation, Hyllus also agrees to. As the play ends, Heracles is carried away to his funeral pyre by a few attendants, with Hyllus asking them to never forget “the great cruelty of the gods in the deeds that are being done.”

A Brief Analysis

Critical opinion of Women of Trachis varies. Even though most think of it to be weak in comparison to any of the other surviving plays by Sophocles, some praise it for its unmistakably Euripidean nature, and admire Sophocles for handling the subject in such a restrained manner.

Indeed, Deianira is much more passionate and wilder in later representations (Ovid, for example), and her depiction as rather a Stoic character here doesn’t do justice even to the etymology of her name: “man-destroyer.” It is difficult to blame Deianira for anything: she explicitly states that she is not mad at Heracles for bringing a younger woman at her house, and it is an exaggeration to say (though it is often said) that the mortal gift for him, the festal robe, is motivated by jealousy—it is, much more, a gift given out of undiminished love. Heracles, on the other hand, is presented as an unattractive hero, entirely out of tune with the times: he sees nothing wrong in bringing Iole to Deianira, and even less in demanding from his son to marry her in his stead.

In some ways, Women of Trachis is similar to Aeschylus’ Agamemnon: a husband brings a younger woman to his house, and the woman avenges the act. However, the comparison paints Deianira in favorable light (unlike Clytemnestra, she neither plans nor wants to kill her husband, has nothing against his lover, and subsequently decides to kill herself), and Heracles in even worse (he is bestial enough to murder his herald, and barely shows any redeeming qualities to the end).

Women of Trachis Sources

There are many translations of Women of Trachis available online, both in verse and in prose; if you are a fan of the latter, you can read Richard Claverhouse Jebb’s translation for Cambridge University Press here. If, however, you prefer poetry, feel free to delve into Robert M. Torrance’s blank verse adaptation here.

See Also: Sophocles, Deianira, Heracles, Shirt of Nessus

Women of Trachis Video

Women of Trachis Associations

Link/Cite Women of Trachis Page

Written by: The Editors of GreekMythology.com. GreekMythology.com editors write, review and revise subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge based on their working experience or advanced studies.

For MLA style citation use: GreekMythology.com, The Editors of Website. "Women of Trachis". GreekMythology.com Website, 09 Apr. 2021, https://www.greekmythology.com/Plays/Sophocles/Women_of_Trachis/women_of_trachis.html. Accessed 26 April 2024.